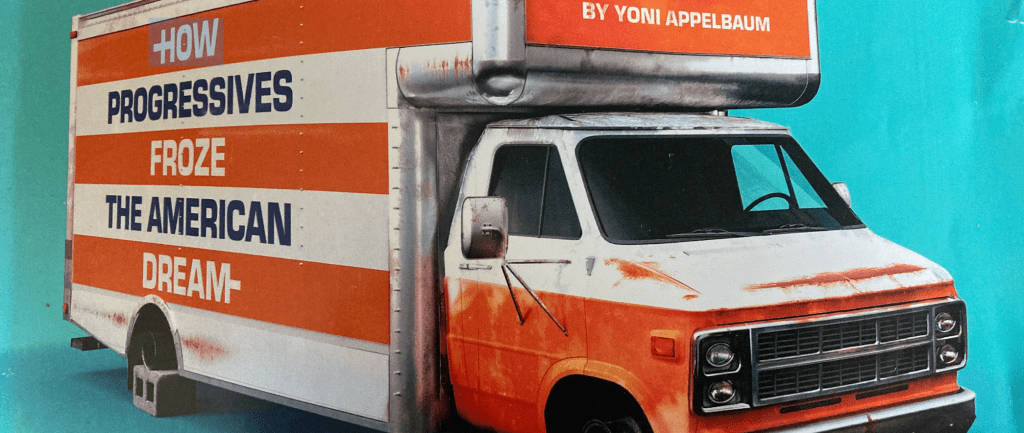

Yoni Appelbaum’s cover story, “Stuck in Place,” in the March 2025 issue of The Atlantic offers a unique thesis as to the fundamental rumblings of our national discontent. That we used to be a society on the move. And now we are not. And that is a problem.

Mr. Appelbaum takes the long view on relocation, all the way back to the one of our guiding national principles: that people came to the United States to escape the rigid hierarchy of wherever they came from, and part of that hierarchy was physical entrapment within the confines of a parochial village. The author describes with glee the nineteenth century American tradition of Moving Day, an unofficial holiday whose date varied by locale, when up to one in five people in any given metropolis switched houses. Most people were renters, who, according to Appelbaum, treated their domiciles then as we treat our cars and cellphones today–consumable items with a constant eye towards an upgrade. He delights in the piles of belongs stacked on streets, profiteering moving men, and the haste required to get out by noon, for there’s a fresh tenant fast on your heels. A giant frenzy of American energy. Personally, I can’t imagine it was all that much fun.

This constant moving was enabled by having a large, relatively affordable, range of housing options in most places were people wanted to live. Another manifestation of resource-generous America. Developers built and the people came. Places got shabby and folks moved on. One striver’s shabby became the incoming immigrant’s dream come true. When a place got entirely too shabby, the owner would tear it down and build anew, usually bigger, taller, denser. Thus our cities grew in a piecemeal fashion.

As did our sense of community. Nineteenth and early 20th century America represented a different kind of community. One based in interest and opportunity rather than heredity. We were a nation where the term ‘stranger’ evolved from someone from beyond, who ought to be feared; to someone new, who is likely interesting.

This idea of constant movement slowed during the 20th century, though it’s spirt remained in our mid-century exodus to the suburbs and our continually creeping West. What brought it to a halt, according to Appelbaum, was Progressives. And the particular example he uses is that heroine of urban salvation: Jane Jacobs.

Before Jane Jacobs wrote her seminal, The Life and Death of Great American Cities, she and her architect husband purchased a townhouse in Manhattan’s West Village, removed the storefront on the first floor, and turned it into a single-family residence. Thus, they both diminished street activity and reduced the number of people living in that space. Nevertheless, they proceeded to make their names championing a kind of dense, pedestrian, street-focused urbanity that their own renovation helped dissipate. They staved off urban renewal and installed zoning, preservation, and other restrictions that discouraged change. They fossilized the neighborhood.

As the “character” of places became important, the affluent enjoyed legal mechanisms to “preserve” their environs. New forms of segregation ensued. Thus today, when less than one in thirteen people move in any given year, we’re an economically stratified nation with woefully inadequate housing stock that continues to reinforce the ‘haves’ and keep out the “have nots.”

According to Appelbaum, we need three million more housing units in our country, and they need to be where people want to live: i.e. big cities. On our current track, we’ll never get there.

I love the idea behind Mr. Appelbaum’s thesis. I appreciate his novel perspective on our national argument with ourselves. I can understand that what he describes is part of our discontent. But I cannot agree it is our foundational problem.

First, we have become a nation of home owners, rather than a nation of renters. This certainly impacts our mobility, and yet I believe most would agree, this is a good thing. Having ‘skin in the game’ makes homeowners less likely to move, and arguably more conservative. We have a stake in preservation over change. I am not convinced that’s all bad.

Second, Mr. Appelbaum doesn’t even give lip service to the ecological implication of adding three million more residences in the United States. In fact, he does not weigh the environmental costs of endless relocation at all. This is surprising to read in The Atlantic, a publication that prides itself on environmental awareness.

Still, the article is valuable and compelling. The pendulum in favor of neighborhood conservation as a euphonism for elitism (i.e. racism) has swung too far. We need more, denser, development in areas where humans have already claimed prominence over nature, and we need to leave areas we have yet to spoil completely alone. Equally important, we need to check our thirst for more space, more privacy. We need to develop new forms of housing, congregate forms, in which we learn how to share both space and resources. Where we build community by living in it.