To Kill a Mockingbird

Concord, MA

Through March 22, 2026

Discount and Group tickets available

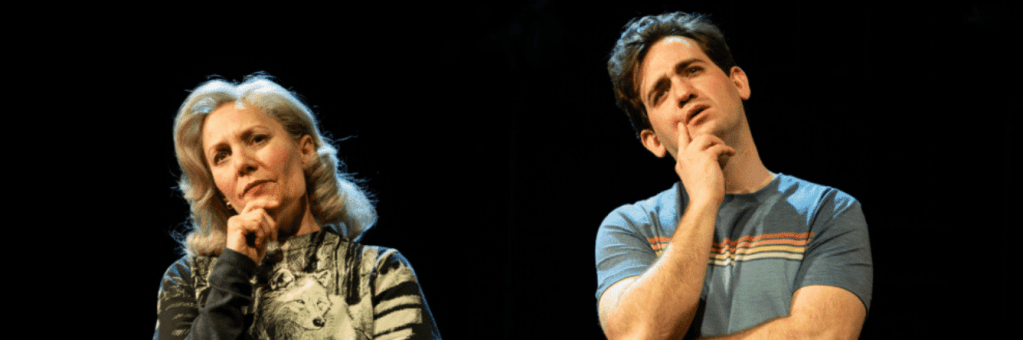

Harper Lee’s 1960 coming-of-age novel, To Kill a Mockingbird is an American classic; it’s popularity only enhanced by the 1962 film in which Oscar-winner Gregory Peck created a stoic American hero: Atticus Finch. I never knew that Christopher Sengel dramatized the book, and that his play has been performed regionally for decades. So I assumed that The Umbrella Stage production of this classic was the much-publicized—and litigated—Aaron Sorkin 2018 Broadway production, in which the story’s focus shifts from seven-year-old Scout Finch to her attorney father. But I was wrong. This is the Christopher Sengel play, and Scout very much holds its center. So much so that two actors play her role: Shelly Knight as young Scout and Amelia Broome as Jean Marie Finch, her adult self, looking back in memory.

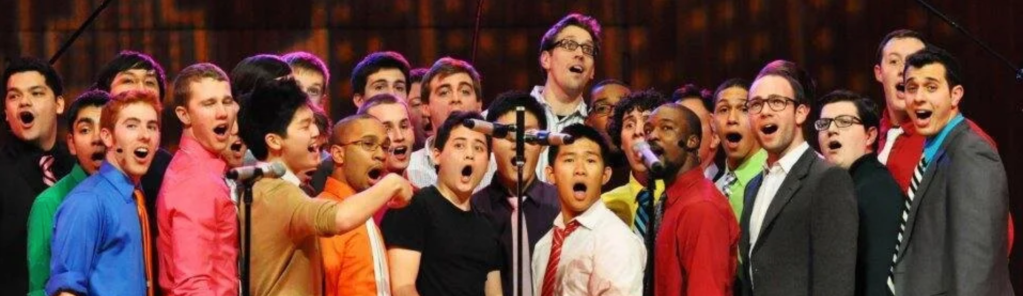

Although there is some adult voice-over narration in the film, in the play Jean Marie Finch is a constant presence and frequent commentator on the action. Within minutes, this device reminded me of a similar American chestnut, Our Town, with Jean Louise filling a role similar to the Stage Manager. Once the connection bore into my head, the parallels persisted. Jean Louise is a filter between the audience and the large cast of eighteen who represent the full spectrum of folk inhabiting fictional Maycomb, Alabama. She holds us at arm’s length from action; where the characters are more archetypes than real humans. Heroic Atticus and damnable Bob Ewell flesh and blood dissolve into their respective symbols of virtue and depravity. As in Our Town, To Kill a Mockingbird climbs allegorical heights.

The sense of remove established by the play’s structure is reinforced by Jean Louise’s commentary. Within five minutes she reveals all the spoilers: that injustice will prevail; and death will ensue. I don’t understand why the playwright chose to divulge so much so soon, except perhaps to reinforce that idea that this is a fable, a stark story of right and wrong, with a lesson to be learned. So, children, pay heed.

The play proceeds with the humid leisure of a Southern summer afternoon, and The Umbrella Stage production embraces that leisure. The set is a collection of front porches with comfy rockers. A cellist punctuates the inaction musically. There’s lots of comings and goings and an awful lot of characters. We are lulled into the idea that much goes on in this sleepy place, though none of it of consequence. The underbelly of attorney Atticus defending a young Negro man accused of raping a poor white woman is but a distant ripple.

There are aspects of Scott Edmiston’s direction that puzzle me. The two young boys are not strong actors, so why have them delver so many lines, unintelligibly, upstage? Why is there a cello when a fiddle feels more appropriate? Why are so many characters climbing up and down porches for short scenes? The play might have proceeded in a more fabled way if everyone simply remained on stage the entire time, stepping in and out of their spotlights as they ebbed and flowed in Scout’s memory.

Nevertheless, Mr. Edmiston and his cast deliver beautifully when the dramatic pitch requires. Despite being forewarned what was to transpire. Despite the production’s pace. The dramatic reveals at the trial stirred my emotions with the same intensity as when I first encountered this story. Clara Hevia as Mayella Ewell and Bryce Mathieu as her accused attacker, Tom Robinson, chill the spine as each delivers their testimony. In their moment, all the distance created by the structure of the play evaporates, and we squirm at the vagaries of human truth.

To Kill a Mockingbird is a fit parable for our current moment. We are presented with a town in which the majority of people are blinded by a prejudice so persuasive they will convict a man they surely know is innocent rather than reckon with their social rot. One man is elevated as heroic as a salve who affirms our essential goodness. And yet, justice does not prevail. True, detestable Bob Ewell is dead. But innocent Tom Robinson is dead as well. And the sheriff chooses to keep the peace by promoting the fallacy that Ewell fell on his knife rather than submit the gentle folk to an uncomfortable truth. We exit the theater stirred by the hope that one good man will bring others into the light. But nothing in the play actually makes that hope real.

Go. See this terrific, thought-provoking production. Emerge with hope. Then act on it.