Fun Home

The Huntington

November 14 – December 14, 2025

Music by Jeanine Tesori

Book and Lyrics by Lisa Kron

Directed by Logan Ellis

The Huntington’s production of Fun Home hits all the right notes and delivers the emotional wallop this tragicomedy deserves.

Fun Home, winner of five Tony Awards for 2013, is based on the graphic novel by Alison Bechdel. I’m not sure why it’s called a novel when the story so closely resembles her life. In fact, three different actors play a character named Alison Bechdel at three different stages of development, often all three on stage at the same time.

The play starts with forty-something Alison, a lesbian cartoonist, light years away from her rural Pennsylvania roots, trying to make sense, graphically and emotionally, of her deceased father. Deceased is too polite a word. Right off we learn that Bruce Bechdel kills himself when Alison, the oldest of four children, is in college.

Early on, the play is schizophrenic, as befits life in Fun Home. Bruce is a prickly dad; an historic house renovator; a high school English teacher; and owner of Bechdel Funeral Home, from which the play’s abbreviated title is derived. Sometimes Fun Home is actually fun, but most of the time it’s a Victorian monstrosity teetering on edge, as the family tries, always tries (and always fails) to meet the unreasonable expectations of a man whose internal conflictions turn cruel toward those he supposedly loves. Early scenes ricochet between family love and family disasters, with Young Alison and her three childhood siblings singing and dancing and hamming it up in the face of trauma.

Medium Alison goes to college. Discovers she’s gay. Treats the audience to the most hysterical coming out scene ever. Then tells her parents she’s gay. No response. Followed by weird response, as Alison’s mother reveals that Bruce has had male lovers throughout their entire marriage. Even before. When Alison returns home, with girlfriend Joan, she anticipates a warm talk with her dad, now that they share being gay in common. Needless to say, that’s not what happens.

Enough of the downer plot. Did I mention Fun Home’s a musical? Really, it is. Though, to be honest, the music’s not all that memorable. Wherein lies the strength of The Huntington’s production. The music is there, and the production numbers with the kiddies are welcome palate cleansers, but Huntington’s focus is on the emotional entanglement between father, mother, and daughter. I’ve seen other productions of Fun Home, but none that left me so distraught at play’s end; so in awe of the human capacity to twist and thwart those we love.

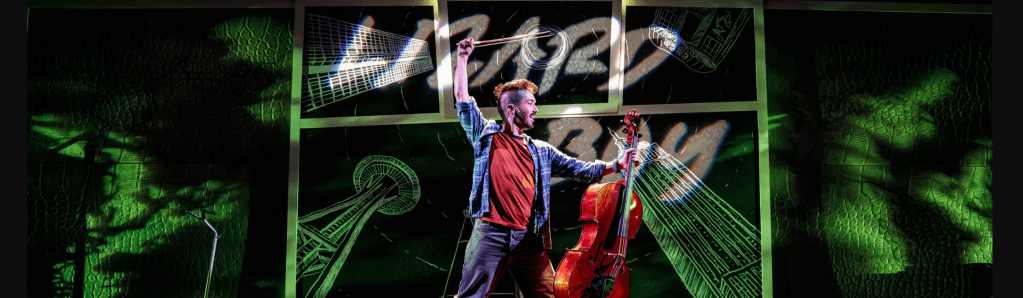

The Huntington set is a remarkable collection of moving parts that assemble and dissemble Fun Home and other locales. I couldn’t figure out the point of the bucolic tree background, nor why the band is framed in a floating sky. Odd, but not necessarily bad.

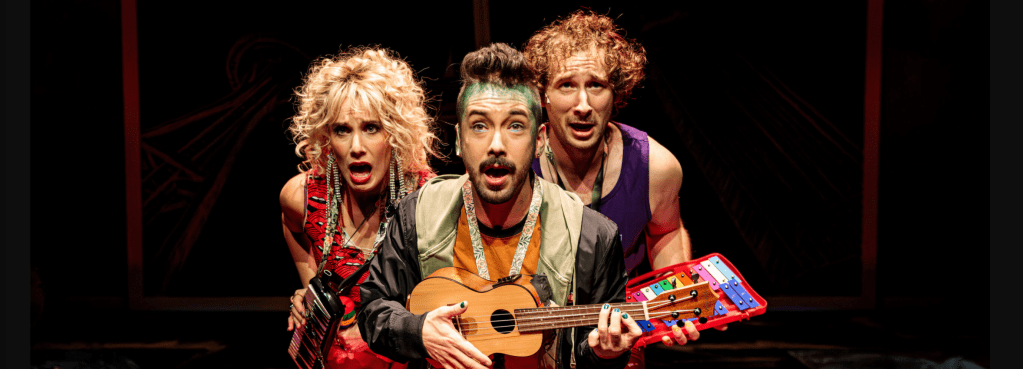

Cast wise, some of the secondary roles deserve more heft. Nevertheless, the three Alison’s carry the show as a perfect trio. Maya Jacobson as Middle Alison is a particular standout. Jennifer Ellis is also noteworthy in maintaining tight composure as the long-suffering wife. She finally gets her own voice in “Days of Days,” which I find the most affecting song in the show.

As to Nick Duckart as Bruce Bechdel, I must confess that I dislike the father in this play so much, I can’t imagine praising anyone in the role. I know a thing or two about growing up under a volatile father. Also about being drawn to men yet marrying a woman, fathering children, coming out, and raising them. It’s not a clear path, but it can be navigated with dignity for everyone involved. When I watch Bruce pick up his former students, and leave his young children alone at night to prowl, my skin crawls. When I see him throw himself in front of a truck, I feel no empathy. Rather, I see the commitments—wife and children—abandoned by this needling, narcissistic man. When I see Alison, so many years later, still trying to reconcile her relationship with the man, I want to scream, “The asshole isn’t worth the effort.” But then I realize that he’s her father, and don’t each of us try to reconcile the sins and mistakes of our own parents, no matter how dastardly they might have been.

You don’t need to be a gay dad, or even be gay yourself, to savor the rich emotional journey into Fun Home. You just need to get to The Huntington by December 14 and be prepared for a deep dive into perdition and forgiveness.